Danish fashion designer Henrik Vibskov was invited to join the fully fashioned knitting R&D programme and designed the installation ‘Observation of Humans’. The work can be seen in the TextielMuseum till 30 March in the exhibition SHAPE – body, fashion, identity.

“I had never heard of the TextielLab,” says Henrik Vibskov, “but three designers in my studio in Copenhagen studied at the Design Academy Eindhoven. They told me I shouldn’t miss this opportunity.” The Danish fashion designer is one of three artists who were invited to join the fully fashioned knitting R&D programme and to work with the TextielLab’s product developers to push the boundaries of knitting techniques and machines. During that process, each artist created a voluminous ‘body-related’ work for the exhibition SHAPE – body, fashion, identity.

Imperfections

SHAPE was opened at the TextielMuseum on November 16. During the opening, the installation developed by Vibskov in collaboration with product developer Mathilde Vandenbussche was unveiled to the public for the first time. At the time of writing this article, Vibskov and his team are working on the assembly in Copenhagen; the knitting was done in Tilburg by the lab team.

Led by Vandenbussche, the team knitted almost 150 metres of yellow and blue checked tubes, which Vibskov is now humanising. These will be filled and given curves, limbs and imperfections. Vibskov doesn’t want the result to be too perfect, he says. “I want visitors to the exhibition to experience that we are all different but still part of the same group.”

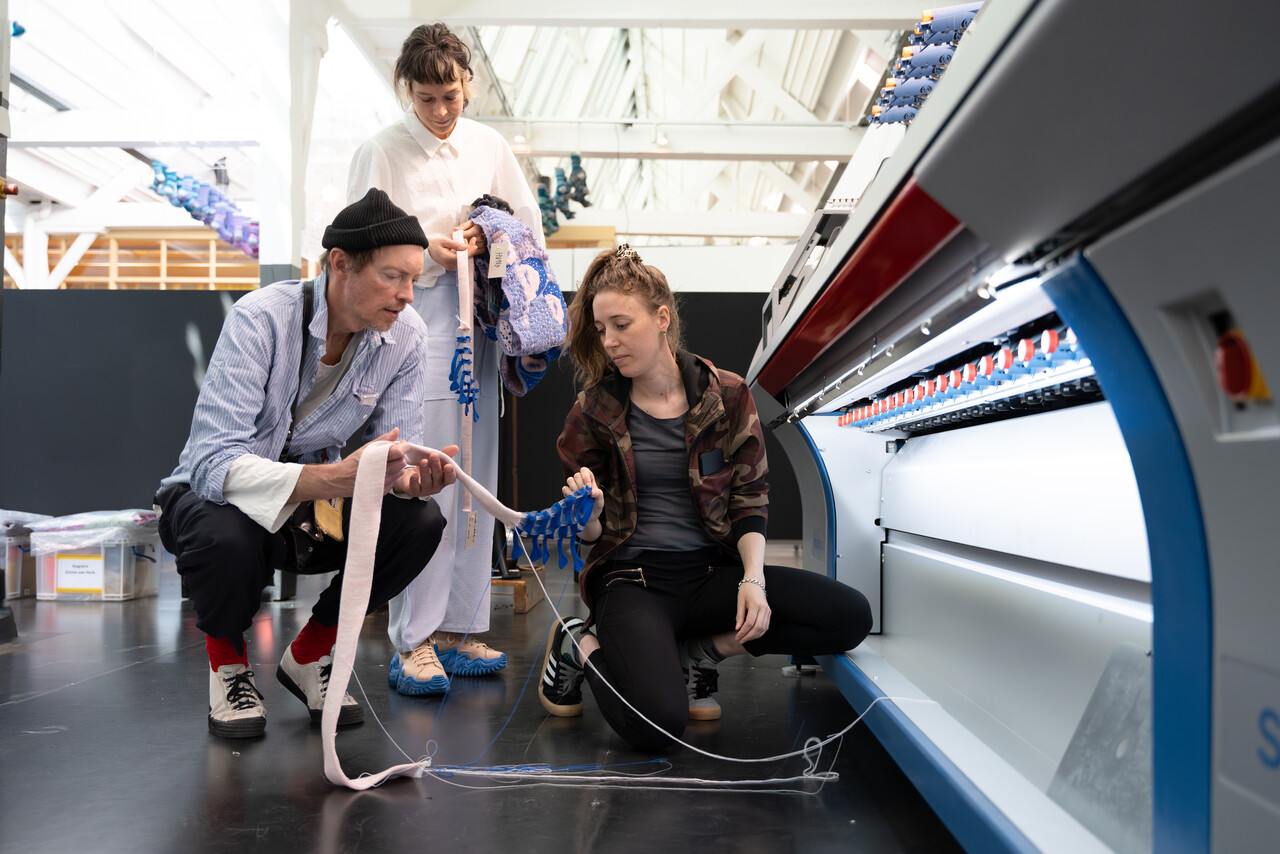

Mathilde Vandenbussche, Henrik Vibskov and his colleague Judith Klingenfeld at the circular knitting machine. Photo: Patty van den Elshout

Checkerboard pattern

The 40-day R&D process that led to the final installation began with a mood board and a series of experiments. Vibskov and Vandenbussche explored the exhibition’s theme – the malleability of the body and the creation of identity – by experimenting extensively with shapes, materials, colours and patterns. “Patterns, the graphic part of fashion, are very important for your identity; they are what make you stand out,” says Vibskov. After trying out various organic patterns, he selected one of the first samples featuring a tight, checked geometric pattern knitted with long floats. “It was a process of making, reflecting, adjusting and readjusting.”

Recycled monofilament

As the R&D progressed, the choice was made to develop a supple, layered knit that plays with transparency and flexibility. To achieve this, the team used a daring combination of monofilament, elastane, fluolurex and viscose, in the most sustainable versions available. For example, the monofilament, which forms a transparent top layer, is made from recycled PET bottles. The first challenge for the lab’s yarn expert was finding that specific monofilament on the right cones for the circular knitting machine. The Belgian company Luxilon, which produces strings for tennis rackets, eventually made the yarn especially for this project. The combination of the smooth monofilament and the stretchy elastic then presented the knitters with a new challenge. “These are both extreme materials,” says Vandenbussche. “To knit elastic, the tension has to be really high, but too much tension will break monofilament. Monofilament is also nearly invisible, so you don’t immediately see mistakes. And it’s extremely smooth, which causes other problems. Knitting with monofilament in such a large quantity is tricky.”

Henrik Vibskov, Judith Klingenfeld and Sarena Huizinga experiment with the installation’s arms.

Photo: Patty van den Elshout

Group viewing

To produce the tubes, which were knitted from a single piece of material, Vandenbussche had to use up to six different programmes simultaneously. With Vibskov as remote art director, 25 tubes were knitted in three variations. In the meantime, product developer Sarena Huizinga produced the limbs on the flat knitting machine. These look like arms or tentacles which are attached to the filled volumes. The arms were also knitted from a single piece of material, right down to the fingers. Using a special method of casting on and casting off stitches, the fingers were carefully shaped to have slightly larger tips or suction cups at the end. By rotating the knitting on the machine, Huizinga was able to spread out the fingers to more closely resemble a human hand.

Six beanbags in the same style complete the installation. Visitors can sit on the bags to view the creatures from below and even lie down to absorb the work as a whole. It will be a wonderful landscape that visitors become a part of, Vibskov predicts. “We struggled with the theme quite a bit during the production process because there were so many angles. This landscape brings together a lot of ideas.”

Text: Willemijn de Jonge